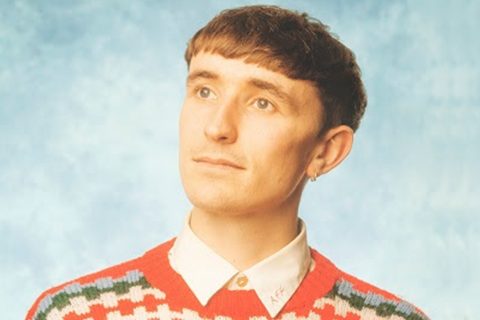

The 2010s brought us a cohort of fresh producers that found themselves in something of an awkward yet revolutionary time. The entirety of musical history could now be accessed on mobile phones, and the gear that made studios of the late 20th-century bankrupt was miniaturised and relegated to a mere feature of music software. For Felix Clary Weatherall, known to us as Ross From Friends, the flare for musical anachronisms couldn’t have come more naturally.

Born in the idyllic seaside town of Brightlingsea to parents with a voracious passion for dance music, it would seem that Weatherall’s path to music production was already paved. His father was a designer of sound systems for concerts, and would tour the UK throwing parties to the soundtrack of various forms of 80s dance music, memories that the producer would immortalise in his video for Pale Blue Dot, consisting of home footage of his parents’ travels.

His first string of singles and EPs as Ross From Friends were abundant with humour, ambiguous sounds, unpredictable song structures and heavily processed sampling. Among these was the sensual yet subtly zany Talk To Me You’ll Understand, which as of now has amassed over 23 million streams on Spotify and another 8.5m on YouTube. Shortly afterwards, Weatherall came to the attention of oddball electronic royalty Flying Lotus, who quickly signed him to Brainfeeder and released the Aphelion EP and his subsequent debut LP Family Portrait months later, which thrusted his tape-saturated antics into a much more introspective, sometimes brooding space. His second and most recent album Tread brings together bittersweet melody with delicate clockwork rhythms and detailed, ever-morphing sound design.

Ahead of a handful of live dates in Australia, we caught up with Felix from Sydney to his London studio, discussing everything from gear to AI and happy studio accidents.

SR: How are you going Felix?

Alright mate, actually on my way to the studio.

SR: Beginning at the beginning so to speak, how do you usually start a track?

It’s a different thing every time, to be honest. Sometimes I’ll just make some drums in the software, or I’ll find a sample and pull that apart. Could be a drone or sound design bit that I really like. A lot of the time I have to just start with anything, just throw anything in, because the track will change so much by the end of it that it won’t even matter what starts it.

SR: You’ve spoken a lot about developing the Thresho software for your own productions, does that help with the process?

I made it in Max 8, and it patches to Ableton, so it basically functions as a plugin. The way it works is it exists on its own channel, and whenever I play something on a synth, as long as it’s going into the interface, it’ll record automatically, and then bank it to the side so I can come back to it later. I’ll be playing around for quite a while, not thinking about the BPM of the track, or committing anything to a particular line. I just wanted to archive everything I’ve done regardless of the session because it might just work in another tune. I knew that it would help me before I made it, and it has so much. It’s always on and listening to me, and gives me back so much material to play with.

SR: It’s a pretty refreshing approach in the current moment with so many third-party algorithms being used for creating things. It’s like you’re trawling your own behaviour as source material for music.

Yeah, and it captures all those naive moves in the process that I’m always trying to recapture. I’m such a sample-based producer, and the idea of taking audio and re-arranging it is really how I work best with music. The AI stuff is impressive technologically, but I do wonder at what point it could take over human art. I think for the simpler tasks where you’re working on a brief with a client, it could potentially pose a threat to those professions, because inevitably the client will go for the cheapest and quickest option, but if you’re talking about fine art it would be interesting to see if AI art could move people in the same way if they didn’t know it was AI. Human beings are still so infatuated with the idea of the manual virtuoso, and I think the whole concept of human perspective still being so valued in art gives me hope that algorithms won’t just take over art, music and everything else.

The fact that it relies so much on other art is another major factor two. It’s like a lot of these algorithms are used to make ‘X in the style of Y’ or something, like say if you wanted to make something like a [Francis Bacon] painting, it would look at all his work and probably do a pretty good job of replicating that style, but the greatness of his art is the fact that all those ideas were his in the first place. It’s the approach, you know? It’s the originality of the approach. All in all, I think with the way things move these days AI art will become really saturated and all the ideas will be done in like 6 months.

SR: Do you think people would listen to AI music?

Yeah, I reckon. I think if people didn’t know it was AI music, you could quite easily get a good generic pop song, or if an artist had a huge catalogue and an AI trawled it all you could do rehashes in their style, but I think ultimately it’s the tunes that stick, both in the pop and club context. When someone comes along and does something really different that’s so exciting for everybody. The thing that makes the next big tune resonate with so many people is so unpredictable, and I just don’t think you could program something like that automatically, you know? I don’t know, maybe it can, but I’m not entirely convinced.

SR: It’s interesting with pop producers, even the most skilled songwriters and producers seem to have backlogs of failed tracks and ones that never charted. It seems hard to formulate what’s going to be big.

You just never know. You can only do stuff and then put it out, and whatever traction it gets is entirely out of your control. I never would have guessed that my earlier tracks would get the play they did. I was just making stuff and enjoying it, and with [Talk To Me, You’ll Understand], I was like “ugh, I really like this”, and was just really enjoying making it. I keep trying to think back at the kind of headspace I was in, and it’s just blank. Like I just checked out, and was just not really present, just following where it went.

SR: When you make most of your tracks, are you usually in this kind of headspace?

Definitely, that’s kind of my initial manifesto. Like when I come into the studio, I try my absolute hardest to reach that state, because I know that’s when I have the most energy. I also make the best music when I feel at my best as well. If I can get myself into that mindset every day, it’s like the days just disappear and the music stacks up. It used to be that I’d spend all day and all night making music, and the next morning I wouldn’t remember a thing about what I’ve just made, and then I’d listen back and be like “oh yeah! I remember that now”.

SR: Looking at parts of your studio, there are so many synths that have been lost to time. Relics of a much more experimental time in electronic music. Do you take a chance on these more obscure instruments or do you have a rough idea of how they behave beforehand?

Yeah, I really do take a risk with all of it. I’m always curious about different instruments and how they might sound, even though they might not be ‘in’. I always just use what I like, and I have to keep that in mind. You can really go down the rabbit hole of YouTube and Gearspace and people are always like “nah, that stuffs redundant, that way of doing it is old, don’t do that.” I’ve encountered that a lot with the drum recording community, oh my god.

SR: From what I’ve seen, a lot of people in online music communities seem to endlessly parrot the “correct” way of doing things, engineering or production-wise.

Yeah, and it’s so different for me myself to tear myself away from it, even though I know it winds me up. People who are like “no, you can’t do it like that. It doesn’t work like that”. Just sit down and experiment, doesn’t really matter how it’s done, you know?

Every time I do one of those instagram Q&A’s, people always ask me “how do you get your mixes to sound like X?”, and honestly it just depends on the content of the track. There’ll be some that I’ve intentionally mixed for a particular purpose, but there are others that are entirely experimental. It’s also such an important part of the process of your journey as a producer to try different things and make mistakes, and to look 10 years back and think “wow that’s actually kind of naive and cool how I thought to do that” and to always move forward with everything you’ve learned. Ultimately everyone is going to have a different sound, and the mix has to cater to that particular situation. The term “mix” itself is so strange to me because it’s all still such a creative part of the process. Like, the amount of reverb and the amount of compression you put on something is a creative decision. It’s all part of the process.

The new creative frontier always comes from a mistake in the studio

The new creative frontier always comes from a mistake in the studio. I was watching this Tony Visconti documentary, and there’s this one tune by T. Rex on Electric Warrior where there’s a really distorted clapping sound at the start. He talks about it, and there was a mic left on the ground near Marc Bolan’s feet in the studio, and he stomped really hard on the ground while they were doing a take, which went really loudly into the microphone into a bus channel on the mixer, and the distortion on it sounds amazing, and it’s the sort of thing I’ve always tried to emulate in my music. I think on a wider scale I want my whole process to be like this. That was one of the things about building this studio with all this gear and live instruments. I really want to feel out of my depth with all this stuff, and to not really know exactly what I’m doing, and leave some of those fuck-ups in there. I wanted to bring it back to when I first started making music, and I had no idea what was going on at all, but that’s the exciting part.

SR: Does chance play a major part in your music? Your tracks are often quite dynamic in tone and structure.

I love the idea of having loads of different layers and being able to listen to an album repeatedly and notice different things about it every time. That’s my approach to listening to music, just getting to know the album down to every little nuance. I like to think that I’ve listened to the music more than the artist, but I probably haven’t (laughs). That’s kind of how I want other people to receive my music as well, so I’m trying to create an overall atmosphere but then put some hidden treasures in there as well.

When I look back at Family Portrait, it seems so dense. At every one point of the album there’s just so much going on. Tread is kind of a reaction to that, and it has more minimalistic sections while keeping my own characteristics like little fills and samples and everything. I wanted parts of the album to be more spacious, and to bring in that dynamic range throughout the album on a whole.

SR: There’s always a kind of damaged euphoria with your music. Often it’ll be uplifting but with a sense of melancholy slightly offsetting it.

My dad always loved to refer to music like that as bittersweet. He has a whole playlist of tunes that evoke that kind of feeling. I’ve always been attracted to that sentiment, where it’s hopeful, but in a darker way. I don’t know what it evokes in me, but I’m just such a sucker for it melodically.

SR: The videos for The Daisy and Love Divide are burned into my head. They’re very dream-like and fit the music flawlessly. How much input did you have with these?

Well The Daisy was actually supposed to be about Rubik’s cubes, because that was a hobby that I picked up during lockdown. I just got really weirdly into solving Rubik’s cubes, and I wanted to learn more about the speed-cubing environment, so we set up this whole thing that was like a fake speed-cubing tournament. It was just a great day of filming it and I was there the whole time, and had a little cameo in it. I wanted to be pretty on-the-nose about what the song was about.

With Love Divide, I just gave the director Bryan Ferguson free rein and just let him work his magic because I’m just such a big fan of his work. The only real brief I gave was that I wanted something quite surreal to go with the track. The video was quite a departure from his other films and he showed me the WIP and I was like “damn this is cool”. It’s not intrinsically linked to the tune as The Daisy was, but I just wanted something visually interesting and surreal.

Comments